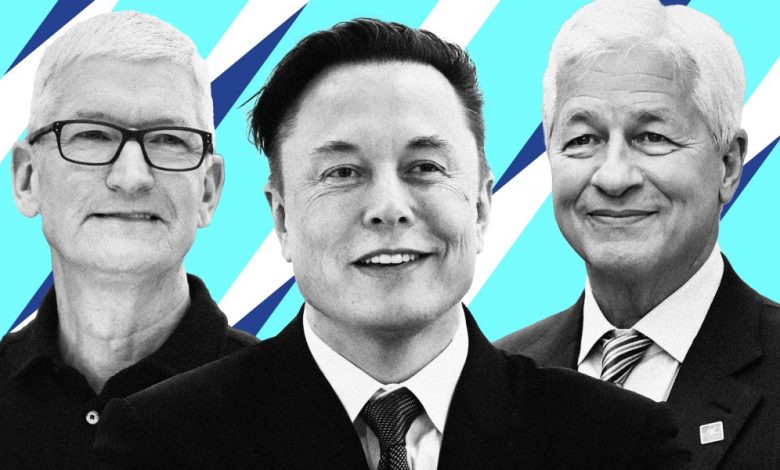

Top CEOs from Elon Musk and Tim Cook to David Soloman and Jamie Dimon have faced the war to return to office in 2022: here’s who won and who lost

In 2022, the world was getting closer to learning to live with COVID-19, and with it more and more pandemic restrictions. In many countries, that meant going back to the office for the first time in two years.

The move away from the government’s stay-at-home mandate has led to companies questioning whether office workers could work from home on a permanent basis. And for many bosses, the answer was very clear: No, they can’t.

With nearly half of America’s CEOs wanting to order their employees back into the office, many companies soon found themselves in a fight between bosses and workers who either ignored return-to-work policies or actively rebelled against them.

Here, wealth takes a look back at how big companies have tried — and in some cases failed — to reintroduce some form of in-person work this year.

Elon Musk, Tesla and Twitter

No list of high-profile returns to office would be complete without mentioning the richest man in the world.

Musk caused a stir in June when he reflected — fiercely — on whether remote work should continue as economies move away from draconian COVID restrictions.

“Everyone at Tesla has to be in the office at least 40 hours a week,” he said in an internal memo to Tesla employees. “If you don’t show up, we’ll assume you’ve resigned.”

It was later reported that Tesla’s CEO received weekly detailed reports on which employees of the electric car company did not show up for work in the office.

However, Tesla’s return to working in person hasn’t exactly been smooth sailing, with many workers showing up to find there weren’t enough desks or parking spaces for them.

After acquiring the company in October, Musk also imposed strict return-to-office mandates on Twitter, sending employees at the social media company an email in November clarifying that he expects them to work at least 40 hours will be in the office per week. Remote work, he told Twitter workers, would be banned unless he personally approved it.

Before Musk’s $44 billion acquisition of the company, Twitter’s policy was to allow its employees to work from anywhere “forever.” Musk, who has since cut Twitter employees by more than 50%, may have had an ulterior motive for repealing that policy: In April, he privately discussed how the move could encourage 20% of Twitter employees to voluntarily resign.

Apple

Apple CEO Tim Cook’s attempts to get the tech giant’s employees back into the office have also been anything but easy.

Over the summer, the company gave its employees a September deadline to be in the office at least three days a week, after earlier deadlines were derailed by COVID-19 outbreaks.

Unlike Tesla and Twitter, which want their employees to be in the office full-time, Apple is aiming for a hybrid model that will see its office workers at headquarters a few times a week. In August, Cook sent employees a memo touting the benefits of “working in person” but backing down from previous, more stringent proposals to include employees on the same fixed days each week.

Rather than placate its workforce, a group of Apple employees responded with a petition arguing that the company “should encourage, not ban, flexible work to build a more diverse and successful company.”

The policy also prompted a top executive to resign from the company, saying he “strongly believed” that more flexibility would have been the best policy for his team.

In an interview with CBS in November, Cook defended Apple’s push for hybrid work.

“We make products and you have to keep products,” he said. “You have to work together because we believe that one plus one equals three. So that takes the fortunate chance of meeting people and sharing ideas and caring enough to have someone else promote your idea because you know that makes a bigger idea.

He added: “It doesn’t mean we’re going to be here for five days. Were not. If you were here on a Friday it would be a ghost town.”

Goldman Sachs

It’s no secret that Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon never viewed remote working as a permanent practice at the bank — last year he called working from home a “deviation” and “not the new normal.”

However, his repeated insistence on staff returning to the office full-time had yet to resonate with employees when the investment banking giant reopened its US offices in February and only half of its workforce showed up.

By October, however, Solomon told CNBC that 65% of Goldman’s employees were in the office any given day of the week — not far from the 75% attendance rate before the pandemic.

Though Solomon seems pleased with the effectiveness of the return-to-office mandate, his employees — particularly young women — are still suspicious of the company’s aggressive push to end remote work.

JP Morgan

In his annual letter to shareholders earlier this year, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said only 10% of employees were permitted to work remotely full-time. About half of the bank’s employees have to be in the office every day, he told investors, while the remaining 40% are allowed to split their time between home and headquarters.

The company made headlines in April when it was reported that it monitors workers’ IDs to find out whether or not they are complying with its guidelines and regularly enters the office.

Dimon, like Tesla’s Musk and Goldman Sachs’ Solomon, has publicly bemoaned how he says remote work has stifled “spontaneous ideation” and leadership and training.

After two years of remote work, Google parent company Alphabet called its employees back to the office in April.

The tech giant told employees it wanted them back on its campus three times a week — and he brought out the big guns to get them on board. In addition to investing $9.5 billion in new offices, the company used arcade games, free food and a Lizzo concert to lure its employees back.

However, road works caused traffic chaos for Googlers for the first week, while some returned to the office to find they didn’t have a desk.

Google’s transition from remote work to its hybrid model also brought a contested reality into play for 17,000 of the company’s employees who had relocated during the pandemic: pay cuts. Employees who left New York or Mountain View — where workers are paid the most — were subjected to pay cuts of up to 25%, depending on where they landed.

L’Oréal

Like Google, beauty giant L’Oréal took a bribe-employee-back approach to establishing hybrid work as its norm.

The French cosmetics giant offers its employees a subsidized butler to help them with private tasks that might otherwise be left out when they return to the office part-time.

For $5 an hour, L’Oréal employees can hire a concierge to pick up their laundry, take their car to the gas station, or take care of their dogs.

L’Oréal offices also offer perks, including a gym, a juice cafe, and an on-site shop that sells beauty products.

Is it important to return to the office?

Rich Handler, CEO of investment bank Jefferies, wrote in an Instagram post in June that those who show up at the office will demonstrate their worth to bosses who may one day decide who to fire.

He also insisted that working remotely could mean the difference between getting a job and building a career.

Handler is not alone in these claims, as experts on the future of work are touting the benefits of a return to the office for Millennials and Gen Z workers.

However, some bosses are just fed up with offering their employees control of the decision.

According to a study earlier this year, 77% of managers are willing to impose “severe consequences” — including firing or reducing their pay — on workers who refuse to return to face-to-face work.