Ernest Shackleton’s voyage was saved by a resourceful navigator

When the wreck of Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance was found nearly 10,000 feet below the surface of Antarctica’s Weddell Sea in March 2022, it was only 4 miles from its last known position, as recorded by Endurance’s captain and navigator, Frank Worsley, in November 1915

That’s amazing accuracy for a position determined with mechanical tools, book-length reference number tables, and pen and paper.

The expedition searching for the ship had searched an underwater area of 150 square miles – a circle 14 miles in diameter. No one knew how accurate Worsley’s position calculation had been, or how far the ship might have gone when it sank.

But as a historian of Antarctic exploration, I wasn’t surprised to find out how accurate Worsley was, and I imagine those looking for the wreck weren’t either.

Navigation was key

The Endurance had left England in August 1914, and Irishman Shackleton was hoping to be the first to cross the Antarctic continent from side to side.

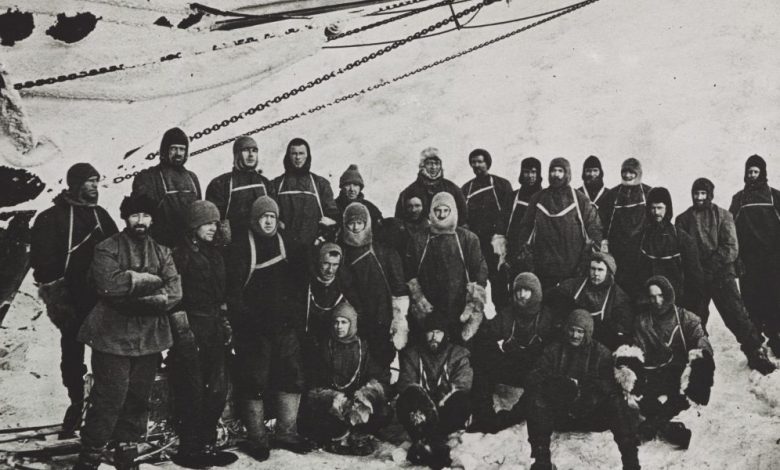

But they haven’t even landed in Antarctica yet. The ship became stuck in sea ice in the Weddell Sea in January 1915, forcing the ship’s men into tents set up on the frozen ocean nearby. The power of the ice slowly shattered the Endurance, sinking it 10 months later and launching an incredible – and almost unbelievable – saga of survival and navigation for Shackleton and his crew.

Shackleton’s own leadership has become the stuff of legend, as has his dedication to ensuring that no man from the group under his command is lost – although three members of the 10-strong expeditionary force lost their lives in the Ross Sea.

Less well known is the importance of the navigational skills of 42-year-old Worsley, a New Zealander who had spent decades in the British Merchant Navy and Royal Navy Reserve. Without him, the story of Shackleton’s survival would likely have been very different.

mark time

Navigation requires determining a ship’s location in latitude and longitude. Latitude is easy to find from the angle of the sun above the horizon at noon.

The longitude required comparing local noon—when the sun was at its highest—with the actual time somewhere else where the longitude was already known. The key was making sure the timekeeping for this other location was accurate.

Performing these astronomical observations and the resulting calculations was difficult enough on land. On the ocean, where few solid points of land were visible, it was almost impossible in bad weather.

So navigation largely depended on “dead reckoning”. This was the process of calculating a ship’s position based on a previously determined position and incorporating estimates of how fast and in which direction the ship was moving. Worsley called it “the seaman’s calculation of courses and distances”.

aspire to land

When the Endurance was crushed, the crew had to get to safety or die on an ice floe somewhere in the Southern Ocean. In April 1916, six months after the Endurance sank, the sea ice on which they were camped began to break up. The 28 men and their remaining gear and supplies were loaded into three lifeboats – James Caird, Dudley Docker and Stancomb Wills – each named after major donors to the expedition.

Worsley was responsible for bringing her ashore. As the voyage began, “Shackleton saw Worsley as the navigating officer, arm balanced around the mast on the Dudley Docker’s gunwale, ready to snap the sun. He got his observation and we waited anxiously while he worked out the sight.”

To do this, he compared his measurement with the time on his chronometer and created calculation tables.

A last hope for survival

When they managed to land on a small rocky strip called Elephant Island off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, they were still starving to death. Shackleton believed the only hope of survival was to get help from elsewhere.

Worsley was ready. Before the Endurance was wrecked he had “worked out the routes and distances from the South Orkneys to South Georgia, the Falkland Islands and Cape Horn and from Elephant Island to the same places,” he recalled in his memoirs.

The men used parts from the other lifeboats to reinforce the James Caird for a long sea voyage. Each day, “Worsley watched closely for the sun or stars to correct my chronometer, upon the accuracy of which our lives and the success of the voyage would depend.”

On April 24, 1916, Worsley got “the first sunny day with a clear enough horizon to look at my chronometer reading.” That same day, he, Shackleton, and four other men set out under sail in the 22.5-foot James Caird, carrying Worsley’s chronometer, navigation books, and two sextants used to determine the position of the sun and stars.

The boat ride

Sailing from one rocky point in the Southern Ocean to another in this tiny boat, these men faced strong winds, massive currents, and choppy waters that could throw them astray or even sink them. The success of this voyage depended on Worsley’s absolute accuracy, based on observations and estimates made in the worst environmental conditions while suffering from sleep deprivation and frostbite.

They spent 16 days of “supreme contention amidst surging waters” as the boat sailed through some of the world’s most dangerous sea conditions, experiencing “mountainous” waves, rain, snow, sleet and hail. During that time, Worsley was able to get only four solid fixes to the boat’s position. The rest was “a fun guessing game” to determine where the wind and waves had taken them and adjust the steering accordingly.

The stakes were huge – if he missed South Georgia, the next country was South Africa, 3,000 miles across the open ocean.

As Worsley later wrote:

“Navigation is an art, but words don’t really name my efforts. …Once, maybe twice a week, the sun smiled a sudden wintry flicker through storm-torn clouds. If I was willing and wise, I caught it. The procedure was: I peered out of our burrow – a precious sextant snuggled under my chest to keep seas from beating down on it. Sir Ernest stood ready under the canvas with chronometer, pencil and book. I shouted “Get ready” and knelt on the thwart – two men held me on either side. I put the sun where the horizon should be, and as the boat frantically jumped up on the crest of a wave, I guessed the height accurately and yelled, “Stop.” Sir Ernest took his time and I worked out the result. Then the fun started! Our fingers were so cold that he had to interpret his shaky numbers – my own so illegible that I had to use memory skills to recognize them.”

On May 8th they saw floating seaweed and birds and then discovered land. But they had arrived in South Georgia in the midst of a hurricane and had to fight for two days to be pushed by the wind onto an island they had been desperately trying to reach for weeks.

Finally they came ashore. Three of the six men, including Worsley, trekked over uncharted mountains and glaciers to reach a small settlement. Worsley joined a lifeboat to retrieve the other three. Shackleton later arranged a ship to pick up the rest of the Elephant Island men, all of whom had survived their own unimaginable hardships.

But the key to all of this, and indeed to the recent discovery of the Endurance’s wreckage, was how Worsley had fought desperate conditions and yet repeatedly managed to figure out where they were, where they were going and how they got there.