Commemorating 100 Years of Our Foreign Service: The Rogers Act of 1924

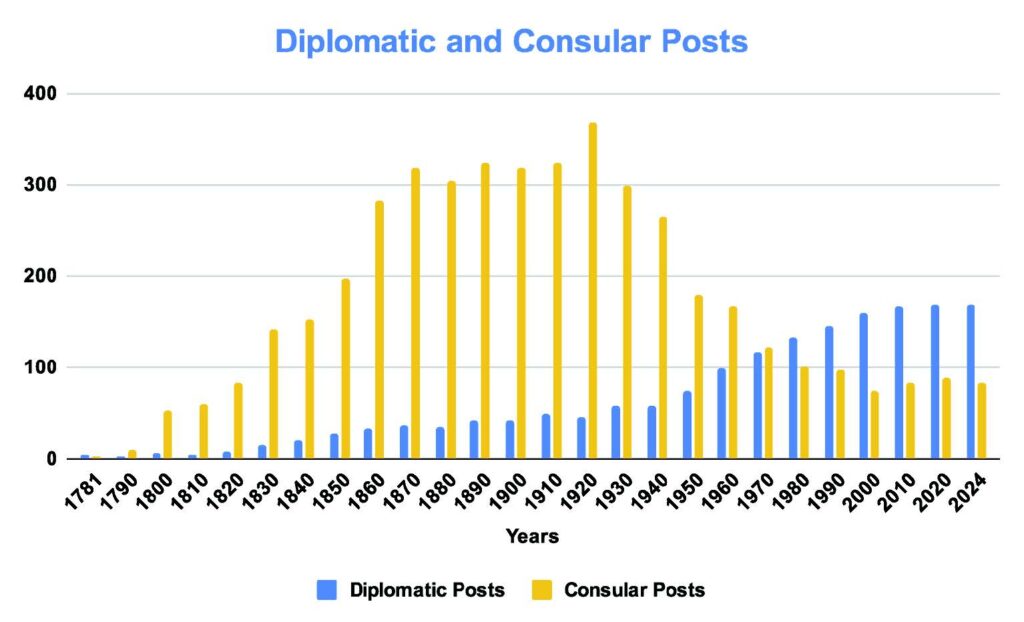

For 130 years before Congress passed the Rogers Act in 1924, American diplomats served in the system established by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson that provided a separation between diplomatic and consular services.

The Diplomatic Service managed relations with foreign governments and was smaller in number than the Consular Service, which handled citizen services and commercial matters. Low salaries, lack of coordination between the two departments and politically motivated

Preference in hiring was the norm.

World War I and the rise of the United States as a world power made it clear that change was needed.

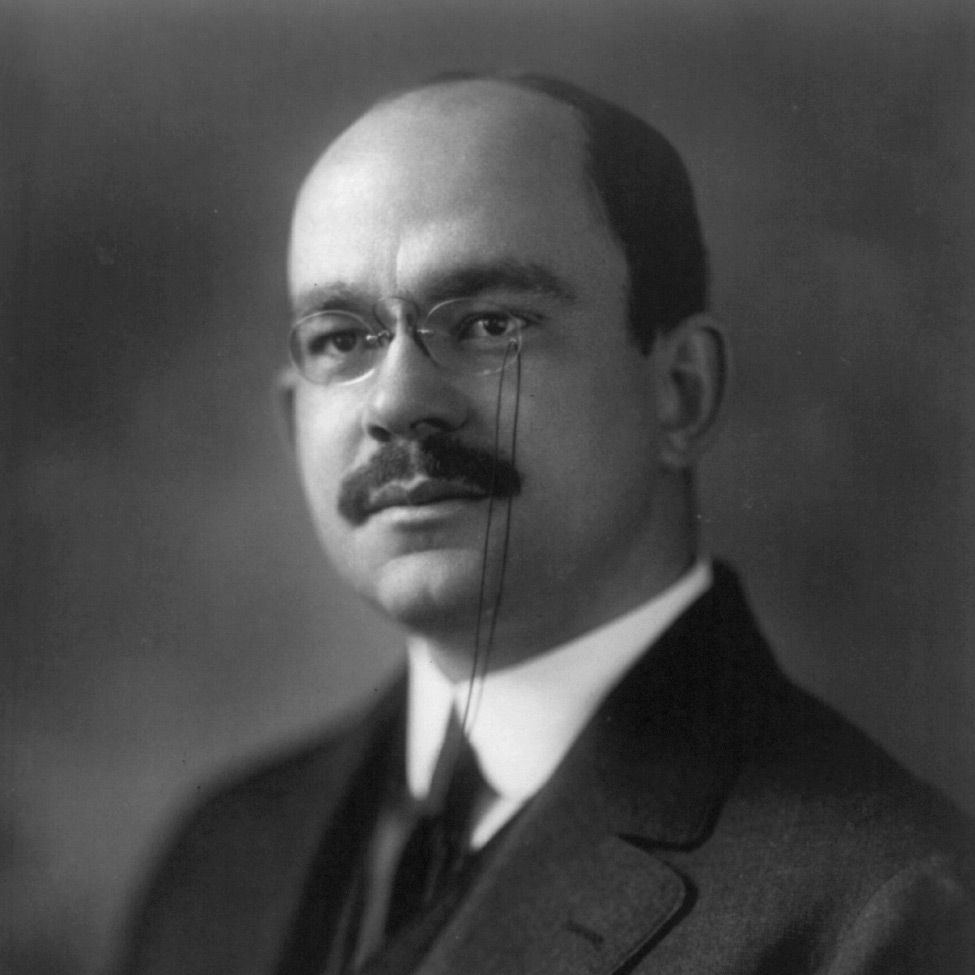

Wilbur J. Carr, director of the consular service, pushed for reform. He found a willing partner in Congressman Rogers, a veteran who believed that a robust, professional diplomatic service was critical to the pursuit of global peace and stability.

The Rogers Act merged the diplomatic and consular services to create the “Foreign Service of the United States,” which established ranks with pay scales, merit-based hiring and promotions, and a pension and disability system.

“… so that the relative merits of candidates can be judged on the basis of their abilities alone.”

– Rep. John Jacob Rogers

Diversity in the Foreign Service

While the Rogers Act provided the legal means for a merit-based system, it would take decades for the Foreign Service to reflect racial and gender diversity within its ranks.

Ambassadors Clifton Wharton Sr. and Frances E. Willis were early notable exceptions.

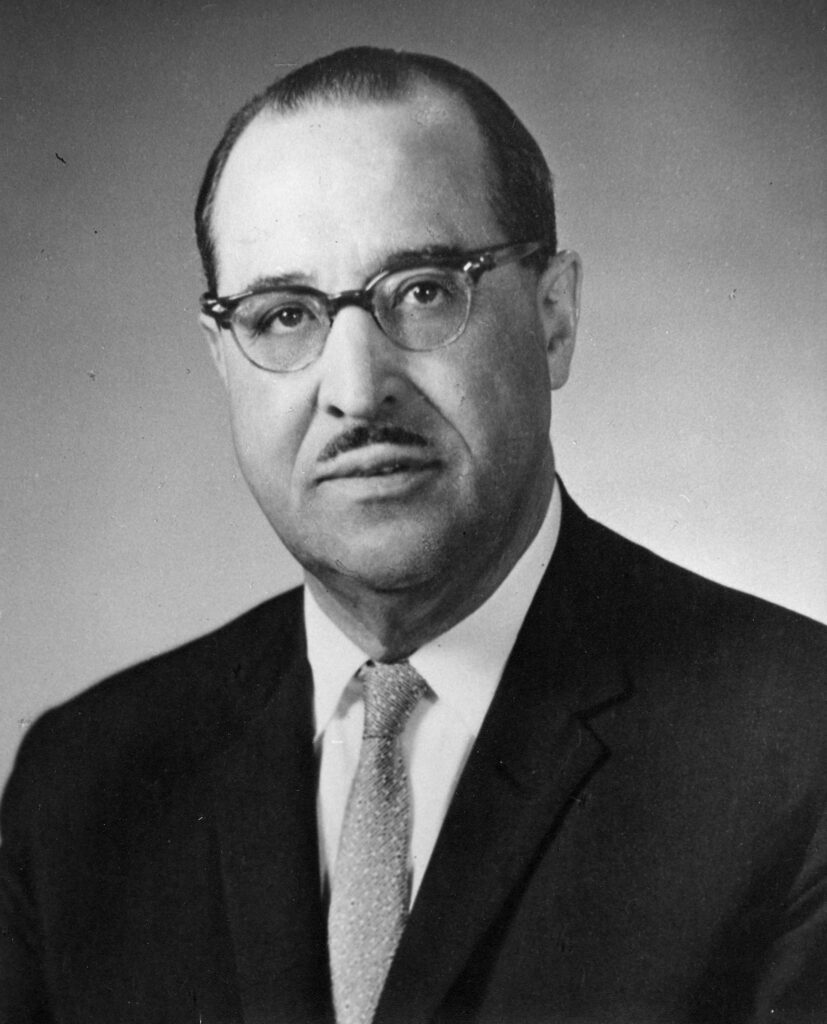

Clifton Wharton Sr.

In 1925, Clifton R. Wharton became the first African American to enter the Foreign Service after the passage of the Rogers Act.

In 1958, President Eisenhower appointed him minister to Romania, making him the first black career diplomat to lead a U.S. mission in Europe. Relations between the two countries were strained as the United States demanded reparations for the damage caused by the communist takeover. Wharton negotiated skillfully a

settlement and caught the attention of Eisenhower’s successor – President John F. Kennedy. In 1961, Kennedy appointed Wharton ambassador to Norway, becoming the first black Foreign Service official to become ambassador.

Wharton received a law degree from Boston University in 1923 and practiced law before entering the Foreign Service in 1925.

The State Department initially assigned him posts exclusively in Africa and the Caribbean, which became insultingly known as the “Negro Circuit.” Ambassador Edward R. Dudley, an African-American politician, formally protested the practice in a 1949 memorandum to the Secretary of State.

That same year, after a long battle with human resources, Wharton was transferred to Lisbon, Portugal. One senior official said, “We don’t need people like him in our posts in Europe.” Despite these examples of blatant racism, Wharton spent the rest of his distinguished career in European countries.

Frances E Willis

Frances E. Willis joined the Foreign Service in 1927. She was the first woman to pursue a career and served at many pivotal moments in international relations.

Many male colleagues praised her diplomatic skills as she rose through the ranks. In 1953, she became the first female Foreign Service officer

Ambassador to Switzerland, a country where women were not allowed to vote. She also served as ambassador to Norway before rising to career ambassador, the highest rank in the Foreign Service, in 1962, while also serving as ambassador to Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

A Ph.D. Willis was a graduate of Stanford University and a professor of political science before joining the Foreign Service. He served for 37 years. While serving in Belgium in 1940 when the Nazis invaded, she discovered that she had “a lot of prejudice that she had to fight against” toward high-ranking male diplomats.

When she briefly headed the U.S. Embassy, she forced an apology from a Nazi general for damage caused to U.S. property at the French Embassy in Brussels.

During her embassy in Ceylon, Sri Lanka in 1962, Willis warned the Ceylon government that the United States would suspend its aid if it did not compensate for the seizure of American oil companies. A TIME In a magazine article on the subject, she was quoted as saying that she believed, “The basis of diplomacy is to be at the same time tactful and sincere.” Eight months later, the United States withdrew aid to Ceylon.

The Foreign Service Test

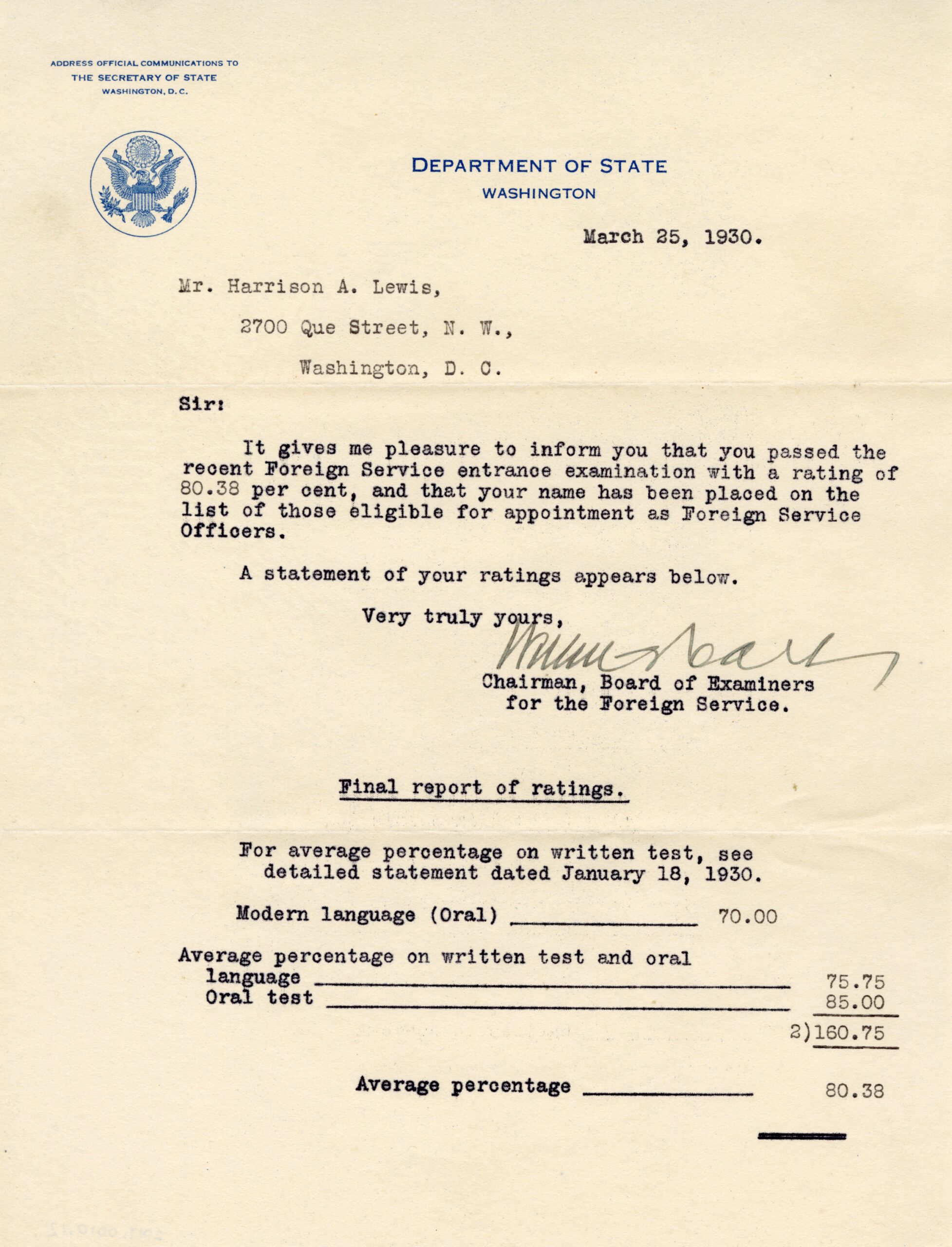

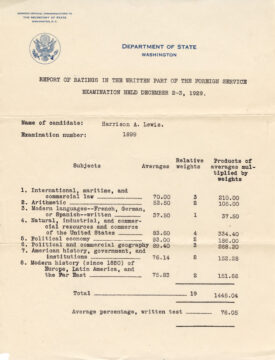

Under the Rogers Act, a two-part exam was the biggest hurdle for any candidate seeking to enter the Foreign Service. The following letter to Harrison A. Lewis, who took the written portion of the exam in December 1929, broke down his score: 76.05%.

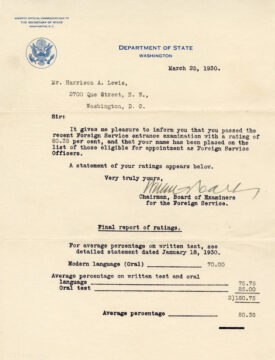

The second part of the two-part exam was an oral exam. Harrison A. Lewis received this result approximately three months after the written test results. With an average of 80.35%, he performed slightly better on this test than on the written test.

Assessment report, written part of the Foreign Service examination. Gift from Robert Cabell Lewis.

Letter, result of the entrance examination for the Foreign Service. Gift from Robert Cabell Lewis.

Training for the Foreign Service

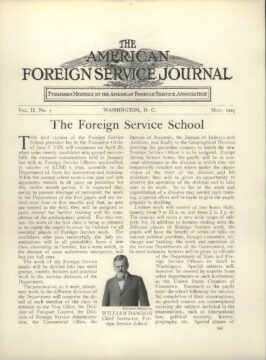

In June 1924, shortly after the Rogers Act was signed into law, President Calvin Coolidge issued an executive order establishing a training school for new Foreign Service officers. The first page from May 1925 American Foreign Service Journal announced and described the school, whose first session began on April 20 with “around twenty candidates who successfully passed the entrance examinations.”

The school’s training program originally lasted one year, but was later shortened to three or four months.

The period immediately following World War II saw rapid growth in the Foreign Service and foreign posts. The following brochure provides an overview of the variety of training courses offered at the Foreign Service Institute – for both foreign and civil service employees – and teaches employees the importance of their participation in training.

AFSA magazine article announcing the first class of the Foreign Service School, May 1925. Courtesy of the American Foreign Service Association.

Brochure “A job worth learning for”, c. 1947-1950. Gift from the family of Ambassador Arthur T. Tienken.

Brochure “A job worth learning for”, c. 1947-1950. Gift from the family of Ambassador Arthur T. Tienken.

Language training in the foreign service

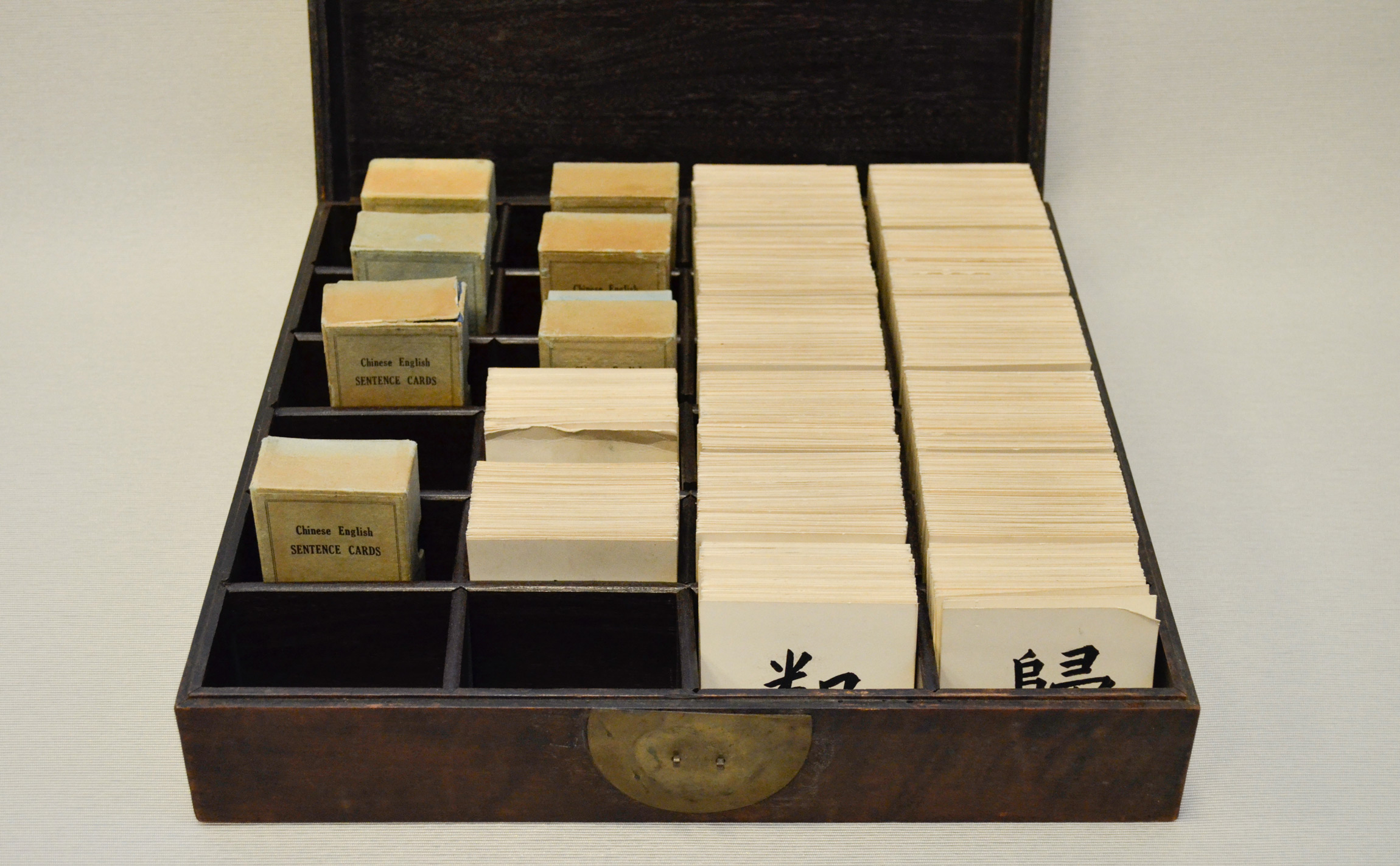

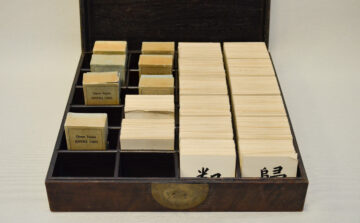

These Chinese-English flashcards are from a set of over 2,000 handmade cards stored in a custom-made box, as pictured here. They were used by a Foreign Service officer who was sent to Peking (Beijing) in 1934 to acquire language skills essential to his diplomatic duties.

All Chinese officers in the U.S. Foreign Service were trained in Beijing from 1902 to 1949, when U.S. diplomatic and consular representation in mainland China ceased.

Language cards. Gift of William J. Cunningham and Kedzie Penfield.

Seal the deal

The Rogers Act merged the Diplomatic Service and the Consular Service into one Foreign Service. This seal, which was used with melted wax, has “American Consular Service” and “Oslo, Norway” written around the Great Seal.

The use of wax seals as part of consular work – once routine – has become increasingly rare over the decades. The US Department of State’s 1999 guidance defined these seals and their purposes: “A small metal seal engraving attached to a short wooden handle and used to make impressions on wax.” It is used to seal premises and Effects in estate boxes, used to seal envelopes and packages or other items as needed.”

Wax seal, American Consular Service, Oslo, Norway. Transmitted from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs.

Wax seal, American Consular Service, Oslo, Norway. Transmitted from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs.

Watch the video to learn more about the US Foreign Service