America’s productivity engine is sputtering. Fixing it is a $10 trillion opportunity

Productivity growth has been weak since 2005, averaging 1.4% per year, compared to the post-World War II average of 2.2%.

That’s a problem. Increasing productivity—economic output per unit of input—maintains America’s competitiveness and improves our quality of life. It is also important to manage challenges such as inflation, debt burdens, entitlements and the energy transition.

Regaining historical productivity growth rates could generate a total of $10 trillion in US GDP by 2030, or $15,200 per US household this year.

It won’t be easy – but productivity is growing fast in some sectors and regions. Since 2007, the information sector has grown at an annual rate of 5.5%. North Dakota’s economy grew nearly 3.5% and Washington’s grew 2.3%. We need to improve productivity on a broader scale.

In order to get the US economic engine running, we must overcome four challenges.

labor shortage And skill gaps

There are two separate but related staff challenges. One is the labor shortage. The labor force participation rate in the US has fallen from 67% in the late 1990s to 62.3%. Only part of that is due to an aging population: More than 5 million Americans are inactive but say they want to work.

The second challenge is that too many current workers do not have the skills they need to be successful. Qualified talent is essential for productivity growth. Over the past 30 years, companies that have invested in people have delivered superior returns. But retraining is a process, not a result. As technology changes, so do the skills people need. Hiring by ability rather than credentials — and eliminating degree requirements, as some states have done — could expand the qualified pool.

Digitization without a productivity dividend

When it works, the link between digitization and productivity is profound: from 1989 to 2019, there was a strong correlation between industries’ productivity growth and their level of digitization.

Information, finance and wholesale, for example, have seen rapid growth in productivity since 2005 and are all highly digitized. It also goes the other way: The construction industry is the second least digitized industry and has hardly recorded any productivity gains for a generation. Digitization also helps individual companies to become more productive. In manufacturing, for example, leaders are more than five times more productive than laggards.

However, many companies that have invested in digitization fail to see the benefits. Our research from 2022 showed that most companies are getting less than a third of the impact they expected from digital investments. Too often, they fail to make the complementary changes in strategy, processes, and training needed to reap the full benefits of digitalization.

Leaders excel at setting bold business goals made possible by technology. They redesign operational processes instead of expanding existing business methods. And perhaps most importantly, they don’t forget the human component: they support individuals and teams to collaborate effectively in these new models.

Underinvestment in intangibles

Technology itself is just boxes and bytes: developing it and then deploying it requires investment in research, intellectual property and skilled people.

Such spending creates a productivity “J-curve” where the initial benefits may be small (or even negative), but the long-term value is significant. But not all companies invest in the first place. Our research shows that productivity leaders invest more than twice as much in intangibles.

Government also has a role to play by clarifying and simplifying regulations and easing restrictions on new investment.

Geographic advantages and disadvantages

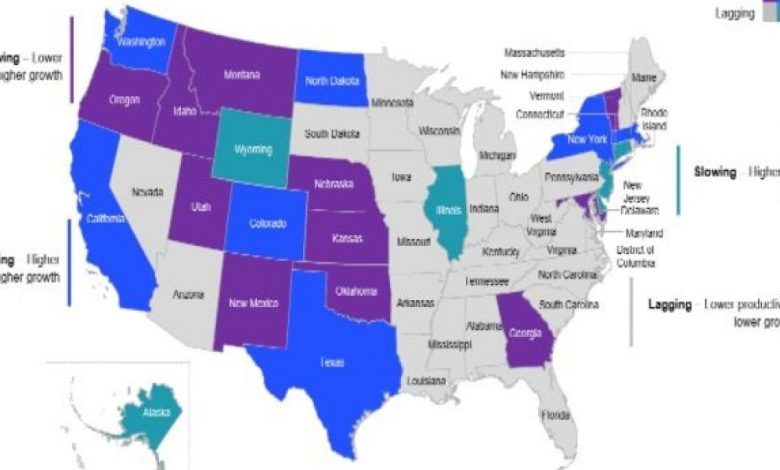

“The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed,” observed William Gibson. And that goes for US productivity. Some states have far outperformed in the last generation. But too many others have below-average productivity and are slipping.

Even within the states, some cities and regions have fallen behind. Such areas often see more than their share of social ills such as lower life expectancy. Even high-productivity cities like San Francisco have failed to share profits equally. The general improvement in productivity is both a social and an economic issue.

Restoring US productivity growth to its historical rate is not impossible. We’ve done it before. From 1980 to 1995 productivity growth was 1.7% and then accelerated to 3% for the next decade.

Increasing US productivity should be seen as a national imperative. We need them to address labor shortages, manage the energy transition, increase incomes, improve competitiveness – and improve the lives of all Americans.

Asutosh Padhi is a Senior Partner in McKinsey & Company’s Chicago office and Managing Partner for North America. Olivia White is Director of the McKinsey Global Institute in San Francisco.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com comments are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of wealth.

More must-read comments posted by wealth:

Learn how to navigate and build trust in your organization with The Trust Factor, a weekly newsletter exploring what leaders need to succeed. Login here.