Particularly exposed to climate shocks, African cities are turning to adaptation and resilience | African Development Bank

Diplomat.Today

The African Development Bank

2022-11-14 00:00:00

——————————————-

Water. Too much, or not enough… In South Sudan, flooding from the tributaries of the Nile in 2021 followed a long dry spell, while Somalia continues to suffer from recurring water shortages. Sandstorms have become more frequent and violent in Algeria, Egypt and Libya, spreading to the cities and even leading to the closure of some ports and airports. On the other hand, floods in the Gulf of Guinea are increasing and causing devastation, as in Nigeria, which has been particularly hard hit this year. In the southern cone of the continent, scarcity of water resources due to persistent drought is jeopardizing the water supply of cities such as Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital. Along the coast, rising sea levels are threatening infrastructure, a trend amplified by the cyclones hitting more and more Indian Ocean countries, especially Madagascar and Mozambique.

It is well known that Africa, while only responsible for about 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, could pay the heaviest price for the global acceleration of climate change. What is less well known is the growing impact of climate change on urban areas, which are already under pressure, especially demographically: as many as 70% of African cities are highly vulnerable to climate shocks… but they are also mainland economic epicenters . And they are still growing.

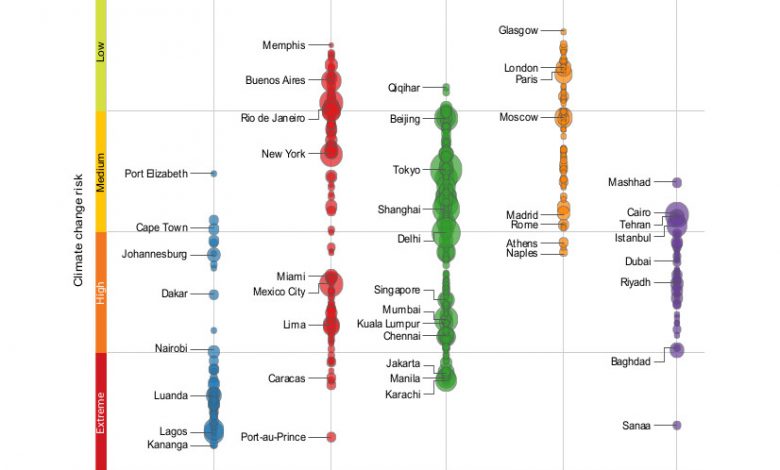

Of the 100 fastest growing cities in the world, the majority of those classified as “extremely high risk” are in Africa.

Climate change: a particularly pronounced threat to Africa’s largest cities

Source: Verisk Maplecroft Climate Change Vulnerability Index ©Verisk Maplecroft, 2021.

Of all the extreme climate hazards threatening African cities, flooding is one of the most significant. Flooding causes significant material damage and affects the most vulnerable populations in informal settlements, which are numerous in African cities that have grown too quickly, and which are often built in high-risk areas, along rivers or on slopes exposed to landslides.

Most of the continent’s megacities are located on the coast. Africa is also highly exposed to rising sea levels. Egypt’s Nile Delta and island states such as the Seychelles are on the front lines, as are important coastal cities such as Saint-Louis (Senegal), Lomé (Togo) and Lagos (Nigeria), a fast-growing megalopolis fringed by lagoons.

Finally, a quarter of African cities are exposed to a high risk of drought, although this does not hinder their growth. Between 2000 and 2030, the African urban population living in arid areas will have tripled in Southern Africa and quadrupled in North Africa; in the intertropical zone it is multiplied by 8.

And it’s a vicious cycle: Droughts are expected to multiply in rural areas as well, fueling the rural exodus that typically swells informal settlements on the fringes of urban centers.

Consequences of climate change for African cities

Source: African Development Bank, 2021.

Let’s go back to the characteristics of African cities, which, above all and contrary to popular belief, offer plenty of opportunities: they have much more to offer in terms of economy, education, basic services and health facilities than rural areas. In addition, they accelerate demographic transition – it is clear that urban dwellers are generally having fewer children than their rural counterparts, as shown by recent studies summarized in Africa’s Urbanization Dynamics 2022: The Economic Power of Africa’s Cities, (OECD/UN ECA/AfDB – 2022)

The other side of the coin is that African cities are coping with rural exodus and are growing at a rapid pace, albeit without the time or resources to anticipate and plan their expansion. This applies to megacities, but also to small and medium-sized cities in Africa (less than 300,000 inhabitants): these are expected to house more than 70% of new urban residents in the coming decades. However, they have much less investment and management capacity than capitals. And while population concentration can be a source of wealth, it can also be a source of vulnerability, especially in informal settlements.

African cities therefore face a double challenge: their efforts to provide basic services and jobs to a growing population in economies where the informal sector most often dominates face climate shocks that will intensify. These shocks also cause water scarcity and damage to existing infrastructure.

African governments are now fully aware of the strategic importance of cities in responding to climate change. A study entitled Urban Development and the African NDCs: From national commitments to City Climate Action, commissioned by the African Development Bank and conducted by the University of Southern Denmark, looks specifically at the place of cities in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) those 54 African countries have submitted to the Paris Agreement. This shows that 49 countries now include urban issues in their NDCs, compared to 41 in 2016. While some of them present strategies to reduce their carbon emissions (particularly in energy production, waste management and transport), it is the issue of adaptation that is being addressed. emphasizes. Water supply, construction of resilient infrastructure and protection of coastal areas are the most frequently mentioned.

Reference to the urban component in the NDCs of African countries

Source: Urban development and the African NDCs: from national commitments to urban climate action, AfDB/SDU, 2022.

The African Development Bank is involved in promoting research on this topic.

On the occasion of COP27, the Bank published a report, Financing Low Carbon and Resilient Cities in Africa, a synthesis of a series of studies that opens up strategic avenues. Better urban sprawl planning and the construction of infrastructure adapted to climate change are identified as two levers with strong transformative potential. Taking into account climate risks in investments can even be an opportunity to create real global urban strategies, in which local communities participate and which strengthen social inclusion. The city must be viewed as a whole and understood in all its interdependencies.

However, the lack of local financial resources remains one of the main obstacles. Cities should develop their own sources of revenue and governments should accelerate fiscal decentralization and support its technical implementation to prepare local governments to manage such budgets.

Filling this investment gap – at least in part – is precisely the role of an institution like the African Development Bank, which has made climate change adaptation one of the cornerstones of its policies. This is evidenced by the adoption in 2021 of its Strategic Framework on Climate Change and Green Growth, which commits the Bank to ensuring that every piece of infrastructure it finances is designed with climate change in mind.

More fundamentally, the Bank is changing its approach to cities: it no longer finances projects one by one, each in their own specific sector, but now considers the urban environment in a comprehensive way, working mainly upstream on issues of urban planning, governance and financial management – again by integrating the climate variable.

To this end, the Urban and Municipal Development Fund, which the Bank set up in 2019, provides African municipalities with the strategic and technical support they often lack to assess climate risks and fully integrate this component into their action plans. The financing of the development plan for the Sheger River, which crosses Addis Ababa, by the Urban and Municipal Development Fund for Preparatory Studies is a good example. A plan to protect an area against a climate risk (in this case flooding) can become an integrated development project, serving the quality of life of the urban population (click here to read more).

This year, new municipalities turned to the Fund for Urban and Municipal Development to benefit from the support program, with the result that they have strengthened their climate preparedness as a first priority. For example, Kanifing in The Gambia, which is exposed to coastal erosion, or the city of Djibouti, which is particularly vulnerable to flooding, will be at the center of the action plans to be developed in 2023. economic opportunities and social inclusion.

The African Development Bank will be presenting some of its findings at COP27, during a roundtable discussion with the World Bank and other MDBs on Wednesday, November 16 at 1 pm Egyptian time (11 am GMT). The event, titled “Uniting to tackle climate change: MDBs, Cities and climate action in Africa”, will take place at the MDB pavilion (streaming link).

The African Development Bank will host another round table discussion entitled “Climate Resilient Infrastructure, Solutions for Low Carbon and Resilient Development in Africa” the following day, Thursday 17 November, from 9:00 am to 10:30 am EGY time (7:30 – 9:30 GMT ), in the Africa Pavilion.

——————————————-